One of our new interns was working on an animation yesterday, and I noticed she was rendering it out at 29.97 frames per second – if you know anything about the systems here in the UK, you’ll know that this can only end badly.

“I thought frame rate just affected how slow or how fast things went” was the reply when I asked about the choice – it seems they picked a preset and stuck with it.

It’s a fair comment, as in many ways that’s true – but there are a lot of factors that go into what we use and when, and the pitfalls of changing half-way, not to mention lighting issues….

The framerate debacle, specifically in relation to international differences, is mostly due to differences in electricity standards – in the UK and Europe, generators all produce electricity at 50Hz (50 pulses a second) whereas in America they all run at a slightly faster 60Hz. I think in the early days of broadcasts (film aside, which we’ll cover later) the camera and transmission outputs were determined based on the TVs’ capabilities rather than the cameras.

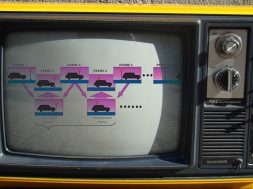

Remember those big old square TVs? They’re called CRT screens, short for Cathode Ray Tube. They’re pretty cool, in that they fire a line of something like X-rays (but not actual X-rays, these are safer) at a silver surface at the front of the box, causing it to glow, either a bit or a lot depending on which part of the screen. This happened over hundreds of lines until an entire picture was on the screen (originally about 300 lines, later more like 500). Because of the limits of these ray firing units, they could get all the lines finished and return back to the top in one power cycle (one Hz). So far so good, right? Except there was a problem – either the TV stations couldn’t transmit the video over the air waves fast enough, or the CRT couldn’t get all the lines out fast enough. So there was a solution – interlacing.

So what’s interlacing? Have you seen 1080p and 1080i on modern TVs? The “i” means it’s interlaced. What this means is that they split up the image so that only half the lines were ever sent in one go – so for example on the first frame they’d send odd numbers, and on the second they would send even numbers. It’s not quite that simple though, as this made things look odd – the way to get round this was they sent the odd numbers of frame one, the even numbers of frame two – and the rest of the data is forgotten about. This means you can get 50 frames or 60 frames per second, whilst only sending half the lines – meaning they could get twice the apparent quality over the same method (usually over the air analog broadcasts).

As HD televisions came into being, the flat panel screens could quite easily display every line in the right order, which is “progressive” – that’s the “p” (720p, 1080p etc) and to most people this looks right – since every computer I know of uses progressive screens, and with the popularity of Youtube and the internet as video mediums, interlacing is a much bigger problem than it was when old TV shows came out. Have you ever seen an old show on Youtube or a modern “nostalgia” show and seen someone moving really quickly and turning into a bunch of horizontal spaghetti lines? That’s a bad case of de-interlacing – that is to say, when interlaced footage is put back together for a progressive screen – a minefield indeed.

Moving back to why we use modern framerate choices, the modern standard in the UK and most of Europe is now 25p – 25 progressive frames per second, whereas it’s 29.97p in America (nearly 30, but with a bit taken out to account for an old bug in the American colour transmission system that’s now not necessary, but they stuck with it because…well…stubbornness).

Why do we still use different framerates instead of just all using the same one? Modern TVs can all now display 50 or 60Hz footage because they’re not tied to the mains like the old CRTs were…. the answer seems to lie in the lighting. UK lights still work at 50Hz, and this means that 50 times a second, a light gets bright, dim, then bright again as the voltage from the wall surges through it to make it light up. We don’t see this with our eyes, as it’s too fast to see – in fact, that’s why the electric standards were made (if AEG and General Electric had just agreed on one number, we wouldn’t have this whole blog).

The problems arise if you’re filming at a different rate to the lights – sometimes the lights are at full brightness, sometimes they’re inbetween pulses, which means what the camera captures, and what you play back later, looks a lot like a horror film…. So it’s easier to try and make the camera run at the same speed at the lights, in that country. This does create an “us and them” between US/Europe, but we largely live with it.

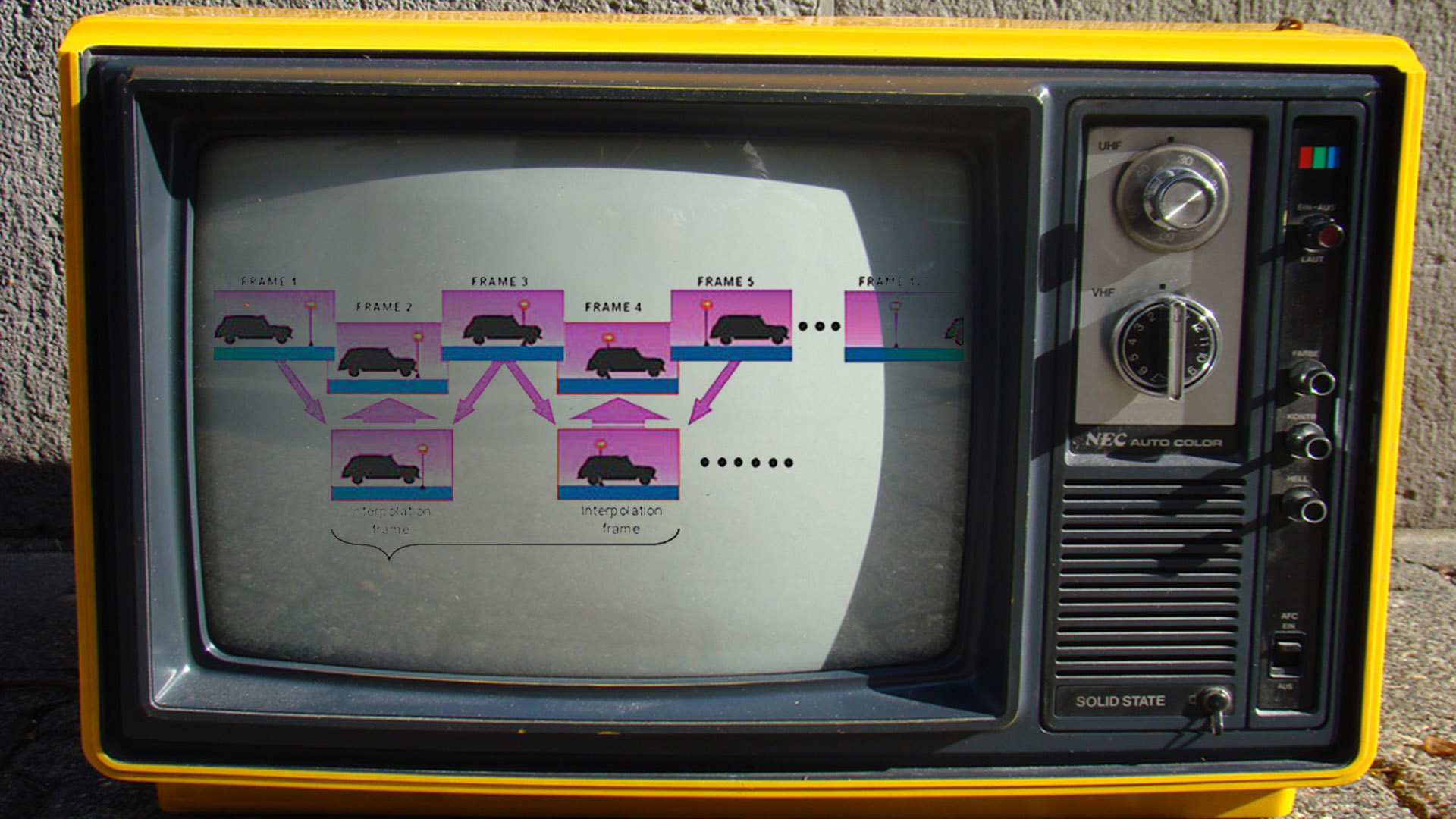

So why with animation do we have to keep to specific framerates? Surely we can do what we want when it’s all virtual? Well, yes and no. We have to pander to the systems it’s going to be playing back on, and what happens if we want to include any kind of real footage in there? If the framerates don’t match, there’s an awful kludge of a solution where the frames are bashed together out of sync (frame blending) or there are more fancy versions, but these always end up making everything look blurry when anything moves. Ever seen an advert from the other side of the pond where everything looks soft and blurry?

As for film, that’s 24 frames per second. Mostly because it divides well (12 frames for half a second, 6 for a quarter second etc) and works well with 60Hz lights (i suspect 24 was settled on in Hollywood, which is, of course, in America.)